By Christi Baron

With all the recent roadwork …with the Elwha Bridge project and all the fish passage projects, Westenders have found themselves grumbling and complaining about delays as they make their trips to Port Angeles and beyond. When compared to what earlier residents of this end of the county had to endure, in order to get to the big city, it is still a piece of cake, even with the delays and the frustrations. Well …maybe …

The first piece of the puzzle that would eventually connect Forks with the rest of the world via roadways was with the completion of the Olympic Highway on the south side of Lake Crescent around 1922. Prior to completion of this road, travelers booked passage on one of Puget Sound Mosquito fleet vessels. After disembarking near Pysht a long road/trail awaited and once in Sappho one could go on to Forks.

For a few years, from 1913-1922, ferries serviced travelers on Lake Crescent, the first The Betty Earles was used primarily to bring passengers to Michael Earles’ Sol Duc Hot Springs Resort. Later, after the resort burned down several other passenger-only ferries serviced travelers. As automobiles became more popular the ferry Marjory began ferrying cars, it held seven autos and 50 passengers!

The largest and last car ferry was Storm King. It held twenty-one autos and 150 passengers. Rates one-way were seventy-five cents for autos and fifteen cents for passengers, kind of pricey for 1922? If one was wishing to travel south from Forks in the early 1900s it was not easy.

There was a puncheon road and crossing of rivers almost certainly meant a ride in a canoe. So, it was also in 1922 that work began on a highway south. In the spring of that year, crews began chunking out the right of way with steam donkeys. Steel and cement were hauled in for the Bogachiel and Hoh River Bridges. Unstable wet ground and huge trees made for slow going. Finally, in August of 1931, the Olympic Loop was completed.

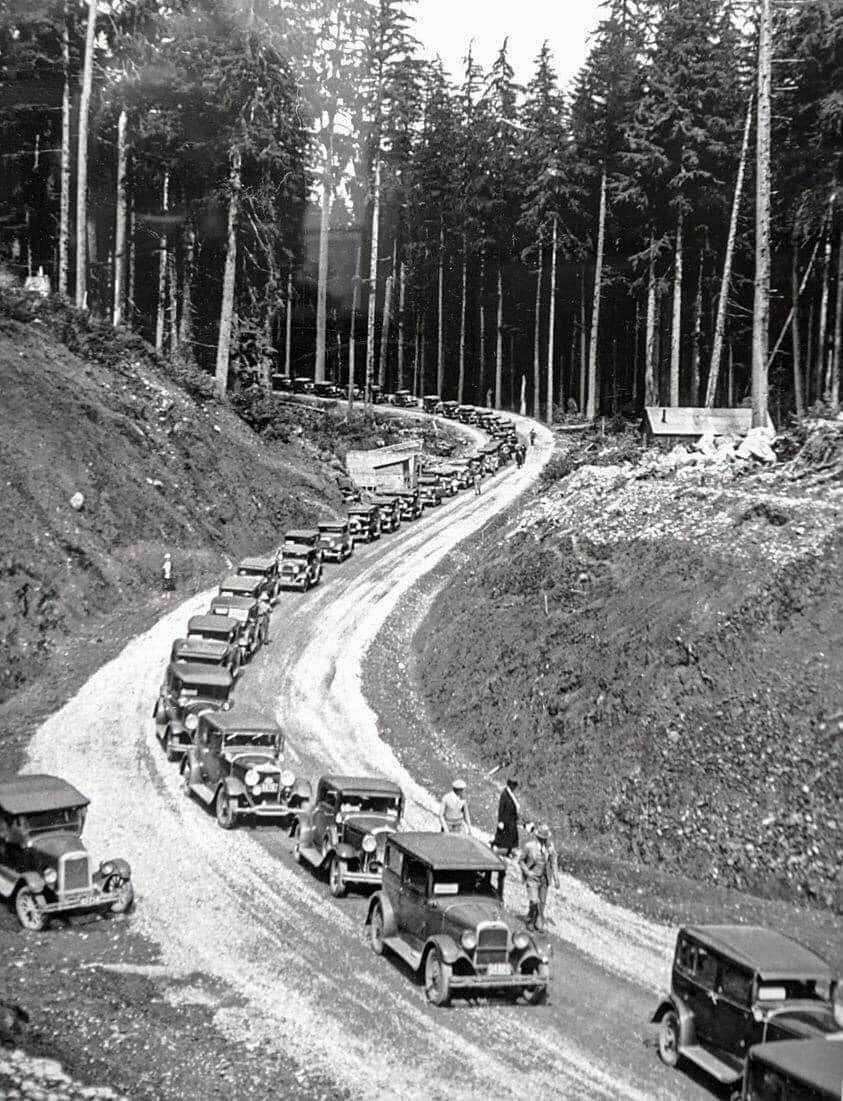

On August 26 and 27 a caravan of an estimated six-thousand cars left Port Angeles. Washington’s Governor Hartley, British Columbia’s Premier Tolmie, Native-American Chiefs, and pioneer settlers all took part. New bridges at Bear Creek and the Sol Duc had dedications and ribbon-cutting ceremonies.

Stopping in Forks at 11 a.m. the entourage enjoyed a “frontier dinner” provided by the Forks Chamber of Commerce. The caravan continued south and the Nolan Creek Bridge was dedicated, they arrived at Kalaloch at 2 p.m. where a huge celebration continued through the next day with dancing, games, and contests.

Highway workers had finally encircled the farthest northwest body of land in the United States with a ten-million-dollar highway project that looped the entire Olympic Peninsula. It skirted a great body of virgin timber lands and an entire mountain range.

But, while it was called a highway, there was a lot of gravel and dust and it was quite a while before the road surface was blacktopped. The Olympic Loop in its final form represented years of work during which time sections of road were pushed through forest wilderness, across bogs and raging rivers and streams, which offered up some of the most difficult obstacles ever faced by western highway builders.

As the Great Depression deepened, road construction projects expanded to provide “relief” to the unemployed. To cover the cost, the State issued its first road bonds in 1933. A reporter dramatically wrote in an article at the time, “Road boosters of half a century and pioneers with the joy of vanished isolation written on their weather-beaten faces joined in, lauding the new highway.”

Also, it is a nice drive when there is no road construction. And, let’s talk about roundabouts…