By Rebecca L. Spang

Professor of History and Director, Liberal Arts and Management Program (LAMP), Indiana University

1918 versus 2020

During the 1918 influenza epidemic, restaurants were actually one of the very few public spaces to be kept open, regardless of other closures.

Some cities held major public events despite the crisis. In Philadelphia, the “Liberty Loan” parade was held as planned, attracting a crowd of 200,000; less than a week later, all of the city’s hospital beds were full.

St. Louis, in contrast, was an early exemplar of social distancing: The city closed schools, churches and other venues where people gathered in large numbers. It effectively kept flu cases to a minimum and “flattened the curve.” But neither Philadelphia nor St. Louis closed restaurants.

In Chicago, football games, wrestling matches – anything considered “public amusements” – were all banned, but restaurants were allowed to operate as long as they offered neither music nor dancing.

Washington, D.C. shut schools, stores and public meetings, but left cafeterias and restaurants open. Dozens of restaurants in the city even agreed to offer a shared, limited menu to ensure that office workers could feed themselves for under a dollar a day: “Prunes, cereal, toast, coffee—30 cents; Ham, cheese, tongue, salmon, or egg sandwich—10 cents; Soup, meat or fish, potato or rice…”

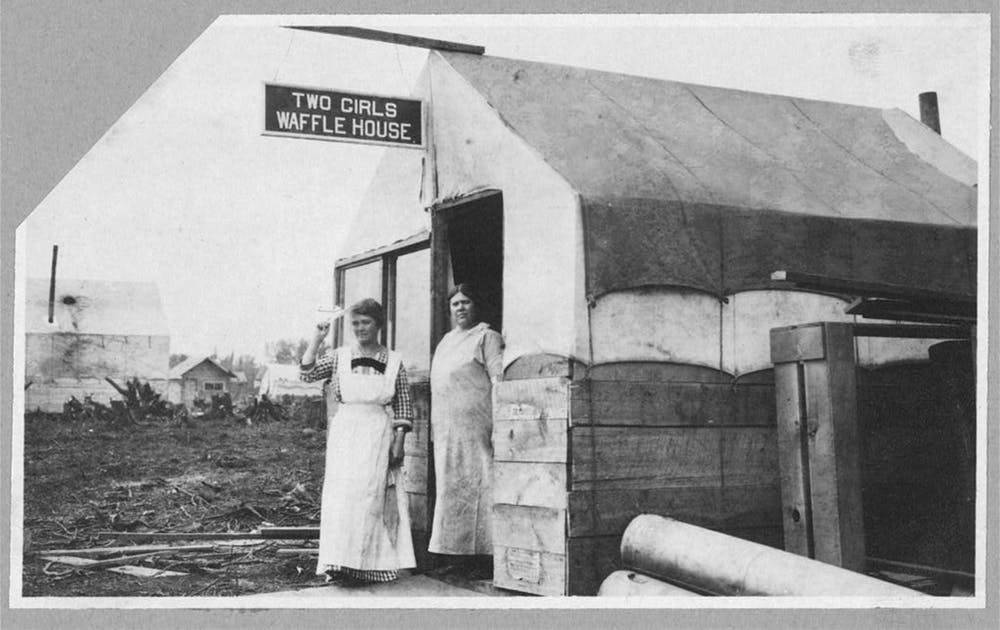

In 1918, when many city dwellers lived in boarding houses and kitchenless studio apartments, restaurants were seen as vitally necessary for continued wartime functioning. They were sites of social solidarity.

In the days of COVID-19, in contrast, restaurant-going is partisan politics. When Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez took to Twitter to encourage social distancing, the one-time Ms. Nevada State, Katie Williams – a school board candidate in Las Vegas – tweeted back: “I just went to a crowded Red Robin … Because this is America. And I’ll do what I want.”

For Ocasio-Cortez and many others, restaurants are chiefly public spaces – places where people congregate. Williams reply asserted that restaurants may be public, but the appetites they satisfy are private and personal. She wanted sweet potato fries and it was nobody else’s business if she had them.

Are restaurants private or public?

The tension between these ways of thinking erupted two years ago as well, when protesters took to heckling administration figures when they went out to eat.

Ever since they first emerged in 1760s Paris, restaurants have, paradoxically enough, been public places where people go to be private. To sit at their own tables, to eat their own food, to have their own conversations.

Restaurants are on the front line in fighting the pandemic today, because they are one of the few sites left where strangers might regularly come into contact with one another. Ride-sharing apps have taken people off mass public transport. The “Retailpocalypse” brought about by online shopping has been underway for years, shuttering brick-and-mortar stores and bringing department stores to the brink.

The National Restaurant Association estimates the industry employs some 15.6 million people. All of those jobs are now on the line, and employers at risk of bankruptcy and permanent closure.

A dehydrated food luncheon at the Senate in 1942. Library of Congress

A world without restaurants?

The coronavirus pandemic might be the end of restaurants as we know them. That should be a cause for sadness and concern not just among foodies and Michelin-star chasers, but for anyone who thinks capitalism and participatory democracy might actually go together.

Since the 18th century, the Western world has been built around multiple, imperfect and only partly compatible forms of public life.

One kind of public is the market: goods available to anyone willing to pay. Restaurants in this understanding are clearly public in a way that private clubs and dinner parties are not.

Another sense of public – “public broadcasting,” for instance – hinges on a common goal and state support. These are characteristics of food relief programs, but not of restaurants.

Many in Enlightenment-era France, where modern restaurants first appeared, believed the two kinds of public-ness were consistent with each other. Markets would expand to satisfy private appetites, and from that would come public benefits: jobs, commerce, coexistence.

Restaurant-going has historically been an experience through which people learned to coexist as strangers. As one American remarked in the 1840s, “It really requires some practice… but these [Paris] restaurant dinners are very pleasant things when you are once used to them.” Praising the cuisine and décor, she was struck most forcefully by the simple act of eating dinner in a room where others did the same.

To be one of the people in that space is to make a claim about belonging in society. Remember that a century later, the civil rights movement sit-ins began at a lunch counter.

The self-styled “inventor” of restaurants, Mathurin Roze de Chantoiseau, often signed himself, “The Friend of All the World.” Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin’s “Physiology of Taste” describes sitting down to dinner as “gradually spread[ing] that spirit of fellowship which daily brings all sorts together.”

These claims have never been fully realized, but for the past 250 years, they have provided consumer culture with a plausible alibi: that it gets people what they want or need.

If the pandemic leaves Americans with nothing but ghost kitchens and GrubHub, we will have abandoned those goals and lost one of the few remaining spaces for coexistence in our fractured country. I, for one, hope that restaurant service has been interrupted rather than terminated.